In the first generation of the Quaker movement, news of the gospel spread across Britain from house to house, city to city. Quickly, the message was taken abroad to the continent of Europe and to the British colonies in the Americas. These early years of Quakerism were characterized by an untamed passion for sharing the good news, inviting others into spiritual communion with Christ and with each other.

This good news spread largely outside of official channels. While Margaret Fell provided practical aid and a communications hub at Swarthmoor Hall, there were not initially formal structures for organizing the wave of evangelism that proceeded from the north of England. The Religious Society of Friends began as an organic movement of the apostolic faith. The Lord called women and men to ministry, and they responded with obedience. Christ used these 17th-century apostles to preach the word and gather his people  together. Everywhere the traveling evangelists went, the Holy Spirit raised up local leaders and established new communities.

together. Everywhere the traveling evangelists went, the Holy Spirit raised up local leaders and established new communities.

Within decades, this burst of pentecostal fervor had established an organic network of Meetings across Britain and the American colonies. Yet, just as this movement reached the peak of its intensity in the early 1660s, severe persecution came. Friends organized themselves in increasingly centralized bodies – Yearly Meetings – as a way to coordinate their response to nationwide persecution, especially in England.

The persecution eventually passed, but Friends’ new emphasis on centralized structures remained. Over time, passionate, evangelical faith diminished and institutional centralization increased, accompanied by an increasing reliance on procedure as a source of authority. Eventually, many Friends would come to believe that it was procedure that defined them. Orthopraxy and institutional authority increasingly usurped the unpredictable guidance of the Holy Spirit.

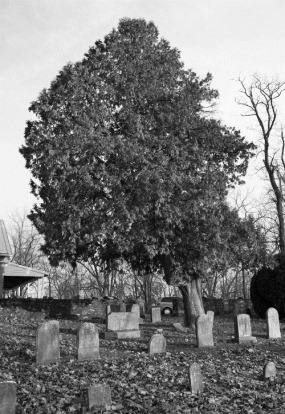

Today, Friends are steeped in the institutional apparatus of former generations. We appoint members to committees and boards. We govern non-profit organizations. We manage historical sites. We are generally nice, respectable, civic-minded people. But where is the spiritual power?

are generally nice, respectable, civic-minded people. But where is the spiritual power?

What happened to the fire that drove early Friends to cross oceans? What became of the radical faith that led women and men to face death, torture and imprisonment? How often are we imprisoned for the gospel today? How many of our Meetings actively support the spread of the good news that Jesus Christ is here to teach us himself? We are often so busy maintaining the institutional legacy of our ancestors that we spend more time keeping up buildings than we do sharing the good news of Jesus with our neighbors.

But that does not have to be the end of the story. Just like the early Friends, we have an opportunity to challenge the status quo and live into the fantastic life and love that Jesus reveals in our hearts and in our life as a community. It is important to remember that those early Quakers we admire so much got into a lot of trouble. They upset people and caused division in their communities. They were not popular among respectable people.

Are we today ready to take the same kinds of risks for Truth that our spiritual ancestors did? How can we support one another in breaking out of business as usual and re-discover the mission that Jesus has for us? What does radical discipleship look like in 21st-century America?