“Let all nations hear the sound by word or writing. Spare no place, spare no tongue, nor pen; but be obedient to the Lord God: go through the work; be valiant for the truth upon earth…” – George Fox

The early Quakers were serious about preaching the gospel. In the first decades of the Friends movement, the message that “Christ is come to teach his people himself” was carried out from the Quaker strongholds in northern England to other parts of the British Isles, America, various kingdoms on the continent of Europe, and even into the Muslim world. Young men and women emerged from the fields and towns where they had grown up and, compelled by Christ’s call in their hearts, journeyed to distant lands whose languages they did not know.

come to teach his people himself” was carried out from the Quaker strongholds in northern England to other parts of the British Isles, America, various kingdoms on the continent of Europe, and even into the Muslim world. Young men and women emerged from the fields and towns where they had grown up and, compelled by Christ’s call in their hearts, journeyed to distant lands whose languages they did not know.

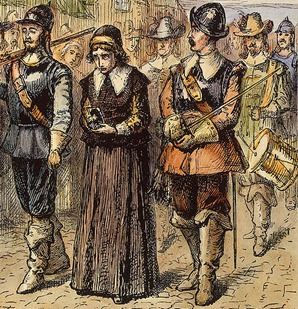

Wherever they went, the early Quaker missionaries announced the arrival of the King of kings, who overthrew all earthly pretenders to the Throne. They called attention to the Lord’s living presence through prophetic signs – such as burning their musical instruments, walking naked in the streets, and heaping burning coals on top of their heads. They preached the good news wherever they could find an audience – whether in the open air, in a crowded bar, or in a government-run church building where they faced beatings and imprisonment for interrupting the state-sanctioned preacher.

the Throne. They called attention to the Lord’s living presence through prophetic signs – such as burning their musical instruments, walking naked in the streets, and heaping burning coals on top of their heads. They preached the good news wherever they could find an audience – whether in the open air, in a crowded bar, or in a government-run church building where they faced beatings and imprisonment for interrupting the state-sanctioned preacher.

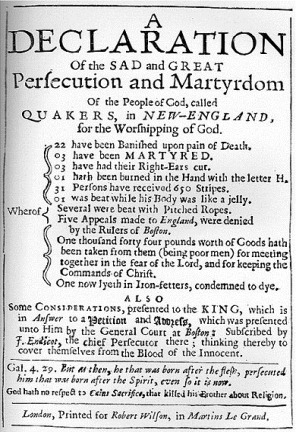

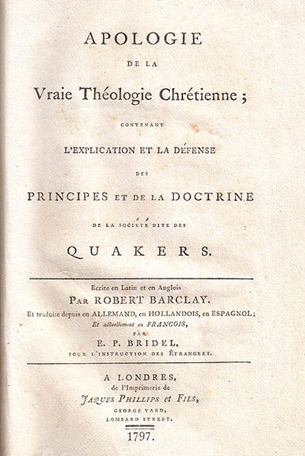

One of the most powerful ways in which the early evangelists bore witness to Christ’s resurrection presence was through the use of pamphlets. During the  turbulent years following Parliament’s execution of King Charles I, England was awash in written propaganda from a variety of religious and political perspectives. Print media was new then, and the early Friends took advantage of it to spread the word of God-with-us.

turbulent years following Parliament’s execution of King Charles I, England was awash in written propaganda from a variety of religious and political perspectives. Print media was new then, and the early Friends took advantage of it to spread the word of God-with-us.

Today, we as Friends in the English-speaking world are, in many ways, experiencing a drastically different context from the Valiant Sixty. We are not, at the moment, living in the kind of intense societal upheaval that characterized the first decades of the Friends movement; and we are not, in general, facing any real persecution for our faith. Perhaps relatedly, we are not – as a general rule – particularly committed to personal evangelism, publicly sharing our faith with the wider culture, or taking risky, prophetic action to witness to the love of Jesus Christ that we have experienced.

How might we today be called to, as Fox put it, “let all nations hear the [gospel] by word or writing”? What might it mean to share the good news of Christ’s literal, teaching presence, both within our own culture, and in the wider world? The Quaker community today is overwhelmingly concentrated in areas of historical British influence – Kenya, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – with Central and South America being the only places where there are significant concentrations of Friends without an historic connection to the British Empire. Why have we as Friends failed to reach beyond the English cultural sphere?

good news of Christ’s literal, teaching presence, both within our own culture, and in the wider world? The Quaker community today is overwhelmingly concentrated in areas of historical British influence – Kenya, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – with Central and South America being the only places where there are significant concentrations of Friends without an historic connection to the British Empire. Why have we as Friends failed to reach beyond the English cultural sphere?

Is the good news that Jesus can be personally known, loved and obeyed unique to British colonial cultures? God forbid! Our faith as Friends is rooted in the belief that Christ’s presence and power is universal, transcending all national, linguistic and cultural boundaries. How, then, can we demonstrate the practical truth of our faith? How can we share this good, universal news of immediate relationship with Christ, both as individuals and as communities?

As different as our circumstances may be from that of the early Friends, we do have at least one thing in common: We are living in an age of new communications technology. Just as the printing press was a revolutionary breakthrough in the seventeenth century, we are experiencing a similarly game-changing technological shift in the twenty-first. How is God calling us to use the internet, and other forms of electronic communication, to advance the gospel in our day?

Just as the printing press was a revolutionary breakthrough in the seventeenth century, we are experiencing a similarly game-changing technological shift in the twenty-first. How is God calling us to use the internet, and other forms of electronic communication, to advance the gospel in our day?

There are signs that some Friends are experimenting with these new media. QuakerQuaker.org is an example of creative use of the online blogging community to draw together Friends and seekers to exchange ideas and develop relationships that can serve the Lord. Another recent, if still embryonic initiative is QuakerMaps.com – which, if further developed and cared for, could serve as a modest platform for outreach to non-Quaker seekers, as well as existing Friends. There are other sites that provide information about the Quaker faith, such as QuakerInfo.org, QuakerInfo.com, and Quaker.org. All of these sites are useful and have the potential to reach many Friends and seekers in the English-speaking world. But what about the other 95% of the world’s people?

There are some signs of hope. For example, Spanish Quaker Luís Pizarro recently began publishing a blog, Cuaquero.org, that is intended to share the gospel message with the people of Spain. Yet, there is still so much that remains to be done. What if we placed an emphasis on training ourselves to be ambassadors to other cultures, learning another language and familiarizing ourselves with another culture? What if we made it a priority to share the gospel message online in every major language, providing resources for learning about Friends’ beliefs, practice, and how to set up a new worship group? Surely Friends already have the capacity to do this sort of outreach in dozens of languages. Are we ready to take the time and effort to live into Christ’s call to preach the good news to all people? Do we still believe that we have received a message worth sharing?