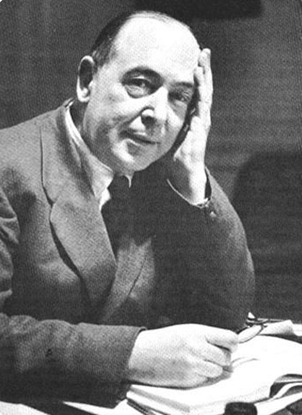

[People] are told they ought to love God. They cannot find any such feeling in themselves. What are they to do? The answer is the same as before. Act as if you did. Do not sit trying to manufacture feelings. Ask yourself, ‘if I were sure that I loved God, what would I do?’ When you have found the answer, go and do it. – C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, pg. 132

In the past few days, I have been reading C.S. Lewis, and these lines really stuck out for me, because they uncover a real difference in emphasis between my own background as a Quaker and Lewis’ heritage as an Anglican. One of the distinguishing marks of the Friends tradition is a strong – almost bull-headed – emphasis on inward, spiritual experience. The Quaker focus on the primacy of the Spirit has often bordered on Gnosticism. That is to say, the spiritual nature of the world has been so emphasized that at times it has been a temptation for Friends to deny the goodness and reality of God’s physical creation.

Spirit has often bordered on Gnosticism. That is to say, the spiritual nature of the world has been so emphasized that at times it has been a temptation for Friends to deny the goodness and reality of God’s physical creation.

This is an understandable slant for Friends, who found themselves up against a seventeenth-century religious establishment that placed all of its emphasis on ritual, written statements of belief and submission to human authorities. If the Church of England was as corrupt as the early Friends made it out to be (and I believe that it was), the Valiant Sixty were right to denounce the empty formalism of the state Church.

Nevertheless, I wonder whether some baby got thrown out with all of that bathwater. Have Friends gone too far in stripping the Christian religion down to its essence? Are some of these outward forms, if not necessary, at least helpful in the development of inward spirituality and Christ-like living?

Lewis sure seemed to think so. His suggestion that, to put it rather crudely, “we’ve got to fake it to make it,” probably makes old George Fox spin in his grave. On the contrary, the traditional Quaker position would be that we should never try to substitute the inward motions of the Holy Spirit with “outward forms.” If we do not feel the immediate presence of Christ, then we should wait in stillness until we do. Then, out of that sense of presence and power, we must allow God to move us to whatever action it is we are to take.

stillness until we do. Then, out of that sense of presence and power, we must allow God to move us to whatever action it is we are to take.

I want to confess: This quietist party line has not been consistently true in my own experience. Most of the time, I experience God as leaving me plenty of room to be self-starting. It is true that there are many times when God intervenes clearly in my life and shows me in a variety of ways how I am to move forward. But it is also true that there are many other times when I do not experience God’s immediate presence in a palpable way. Yet, even in these times, I am often required to make decisions. In such cases, I do my best to make a faithful decision, based on my prior experience of God. Relying on my present level of understanding of God’s character and will for my life, I chart my course and pray that God will correct me as soon as possible if I am wrong. And God has a tendency to do just that!

My need for trust – faith – without the benefit of an immediate sense of God’s presence is most clear in times of spiritual crisis. There are times when the darkness in my life is thick and almost overwhelming. Much of the holiness that I have experienced seems overshadowed and God feels distant. I have two choices in times like these. I can make the decision to despair, surrendering myself to the darkness and cursing God, or I can choose to respond in faith. If I respond in faith, I must respond as if. In times when God seems so far away and evil seems so much more real, I must persevere in willful confidence that the power of the Lord is indeed over all – even if my immediate experience indicates the opposite.

Even in less extreme cases, I believe that there is an argument to be made for living as if. On a day to day, week to week basis, I do not always feel God’s presence with me. There are many moments, not just in times of intense crisis, when I must rely on previous experiences of God’s power and love and carry on in trust that God is still present, even if I do not feel particularly in touch with the Spirit that day.

not just in times of intense crisis, when I must rely on previous experiences of God’s power and love and carry on in trust that God is still present, even if I do not feel particularly in touch with the Spirit that day.

It has been my experience that the Light of Christ is a refiner’s fire, purifying us and changing our very natures. Over time, as we yield ourselves to the working of the Spirit in our lives, Christ transforms our natures, restoring our personalities to the state that God intended. As this process moves along, is it possible that God gives us opportunities to exercise the increasingly redeemed natures that are being re-created within us? It seems from my experience of this process that God periodically removes our training wheels. God gives us the freedom to experience the full possibilities of life in Christ.

This makes sense, doesn’t it? As Christians, we believe that God desires us to freely choose relationship with God. It seems that the Lord is truly pleased with our free choice to love God and to imitate his Son, Jesus. It would be very difficult for us to freely choose to love the Lord if the Spirit were constantly overriding our faculties with states of ecstasy and connection, just as it would be very difficult for a child to truly love their parents if they were smothered with gifts and attention morning, noon and night. It seems that God gives us space so that we can love God for who God truly is, not merely for the gifts that God bestows.

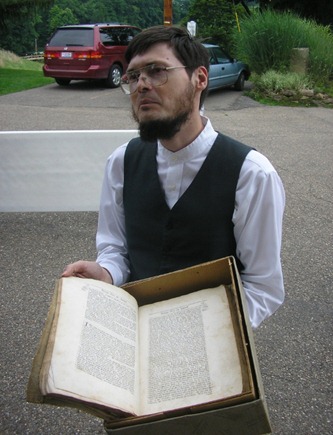

While all of this seems very clear to me, I recognize that it presents some complications for Friends. Our emphasis has always been on complete submission to the Spirit. Indeed, at certain points in our history it seems that Friends felt they needed an inward motion of the Spirit to go to the outhouse! I will admit that I do not have that kind of relationship with God. While God is very active and present in my life, there are many times when I simply do not feel the Spirit’s presence. What am I to do in these times?

not have that kind of relationship with God. While God is very active and present in my life, there are many times when I simply do not feel the Spirit’s presence. What am I to do in these times?

Is it sometimes appropriate to live “as if” we loved God? As if we felt his presence? As if we believed the teaching and example of Jesus as we find it in the Scriptures? The very thought of putting belief first and finding inward experience afterward is, at least at first glance, an affront to traditional Friends doctrine. But what is that to us? Are we looking for Truth, or will we only accept the opinions of our Quaker ancestors? What canst thou say?