For almost two weeks, the eyes of the world have been focused on the daylight execution of a black teen by a white police officer, the outrage of the African-American community, and the heavy-handed, militarized response of the local police force. With each day that passes, it becomes clearer that the mess in Ferguson speaks directly to the continuing struggle that all of us face – as individuals, communities, and the nation as a whole – as we seek to address the wounds of generational injustice, violence, and race/class hatred.

For almost two weeks, the eyes of the world have been focused on the daylight execution of a black teen by a white police officer, the outrage of the African-American community, and the heavy-handed, militarized response of the local police force. With each day that passes, it becomes clearer that the mess in Ferguson speaks directly to the continuing struggle that all of us face – as individuals, communities, and the nation as a whole – as we seek to address the wounds of generational injustice, violence, and race/class hatred.

I have hesitated to write about Ferguson, for several reasons. First of all, I’m a white guy, and the last thing this conversation needs is another white person lecturing about the oppression of black people. No matter how well-intended, white discourse on the reality of racism is fraught with difficulties. Simply put, I will never know what it is like to be black in America.

Another reason I shy away from writing about Ferguson is that it is controversial. Believe it or not, I find it uncomfortable to wade into matters of public debate – particularly those that have taken on a political tone, as this current crisis has. No one in their right mind wants to invite the kind of hate-mail that is inevitably generated by discussions of hot button issues like racism and structural injustice in the United States.

Finally, I have hesitated to write about events in Ferguson, Missouri because to do so would force me to be vulnerable. For me to write authentically about the scourge of racism, I must wrestle with the many ways in which I participate in racism – both structural and personal. To talk about racial inequality demands that I face my own complicity in systems of oppression that go back centuries, but which still have us in their grip today.

Finally, I have hesitated to write about events in Ferguson, Missouri because to do so would force me to be vulnerable. For me to write authentically about the scourge of racism, I must wrestle with the many ways in which I participate in racism – both structural and personal. To talk about racial inequality demands that I face my own complicity in systems of oppression that go back centuries, but which still have us in their grip today.

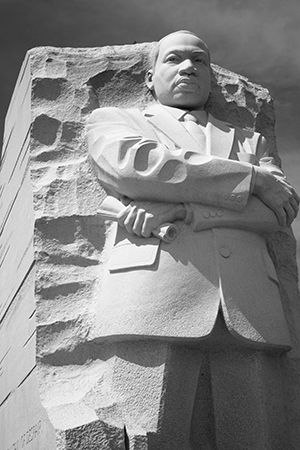

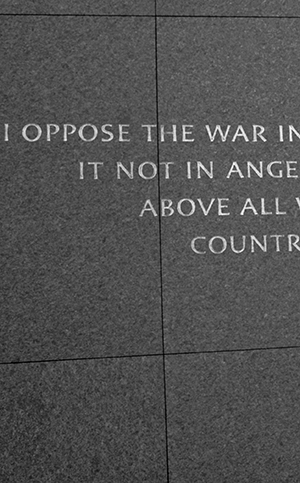

This is scary stuff. While most Americans have become increasingly comfortable with the idea that our country once had a problem with racism, it is challenging to confess that we still find ourselves captive to the spirit of race-based oppression. We remember proudly how our country lopped off the branches of chattel slavery in the 1860s, and we glory in the civil rights movement, which cut down the trunk of Jim Crow a century later. But it is harder to recognize that beneath that monumental stump there is a profound root structure of injustice that coils tightly around us as a society. No number of memorials to Martin Luther King built atop that stump will remove the roots that choke our nation’s soul.

The crisis in Ferguson presents white Americans like me with an opportunity to wake up to the reality of ongoing, structural racism in our country. Slavery is formally abolished, and Jim Crow is no longer the law of the land, but the spirit of both are alive and well in our cities: In police forces that target our black neighbors and occupy their streets with counterinsurgency-style tactics; in our cities that are sharply segregated by race and class; in a prison system that disproportionately jails black men; and in all the subtle ways that I as a white person am taught to fear and look down on blackness.

Seeing is always the hardest part. This is why the first of the 12 Steps is admitting we have a problem. The first phase of Jesus’ ministry is to call us to repentance. The first step of the Quaker spiritual path is to stand still in the light, allowing it to show us our darkness. If we are willing to acknowledge the challenge that we face, the Holy Spirit will give us power to change, digging up the roots of evil and planting seeds of righteousness.

Seeing is always the hardest part. This is why the first of the 12 Steps is admitting we have a problem. The first phase of Jesus’ ministry is to call us to repentance. The first step of the Quaker spiritual path is to stand still in the light, allowing it to show us our darkness. If we are willing to acknowledge the challenge that we face, the Holy Spirit will give us power to change, digging up the roots of evil and planting seeds of righteousness.

Are we ready to see yet? As white people, can we resist the temptation to blame black Americans for the conditions of their oppression? Will we choose to avoid the pitfall of framing this crisis as a question of (other people’s) personal responsibility, rather than being primarily structural – a system that we each bear some personal responsibility to deconstruct?

As a Christian, am I willing to acknowledge that Jesus was executed in public after being accused of insurrection against the state? Am I ready to acknowledge the echoes of the cross in the way that modern-day authorities brutalize my brothers and sisters in Ferguson? Am I willing to bear that cross, in some small way, even if it simply means taking an honest look in the mirror and repenting of the seeds of racism that are present in my own life?