Dear friends, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God… – 1 John 4:1a

I do not think of myself as being particularly nationalistic. Though I love my city, my region and my fellow US citizens, I am suspicious of national pride. I do want the nation in which I reside to be a model of justice and generosity for the international community, and I can feel proud of the United States when it demonstrates compassion, ingenuity and ideals worthy of emulation. And it often does.

This kind of national pride seems healthy to me. It is appropriate to appreciate the positive traits of myself, my family and my wider communities, and I can appreciate the many things that make America a good place to live. Self-esteem, in right measure, is a good thing.

But there is a kind of pride that goes beyond healthy self-esteem. There is pride that discounts the value of others, that lifts itself up by tearing others down. This is the kind of pride that goes before a fall. On the individual level, it can lead to selfish behavior that ignores the needs and concerns of others. On the international level, such pride can cost millions of lives – through war, famine, preventable disease and suppression of human rights.

Projected onto the world stage, this pride often passes as “patriotism.” Under the banner of loving our country, we are encouraged to project all fear and darkness outwards. The unknown “other” becomes the focus of all of our hidden shame and anxiety. We begin to see ourselves as innocent and heroic victims, assailed without cause by people and nations that hate our way of life. In the United States, this form of fear-drenched pride was especially prevalent in the years following the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Our government called us into a righteous “crusade” against an externalized evil.

I would like to believe that I am immune to such appeals. I was raised in a family with a very developed critique of patriotism and Empire. From an early age, I have been inoculated against the seductive battle cries and lies that politicians habitually tell when a nation is gearing up for war. Yet, despite my deep resistance to patriotic feeling, I must confess that the attacks on the United States’ embassies in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula have shaken me.

I was deeply affected by the news that the US ambassador to Libya was murdered, and I recognized a strange feeling emerging from somewhere deep inside. To my surprise, I identified this feeling as the exact sort of patriotism that I have resisted for so long.

I think about what this patriotic sensation feels like in my body. I experience a constriction in my chest, a gut-level shock that someone would strike me in Libya. Yes, me. Despite all my training, it feels like a personal attack. The ambassador was not just an individual. He represented me, my family, and all Americans. To strike him was to strike all of us. Somehow the fact that the killing took place within the embassy makes it even worse. In some strange way, I feel as if my home has been broken into.

In addition to these feelings of violation, I experience positive feelings, too. I feel drawn deep into the community of American citizens. Somehow, we are all made one in this event. Despite the terrible sensation of collective violation, I feel another emotion, even more surprising: Euphoria. This attack makes me feel strong, because it bonds me with 300 million others who are the object of this crime. Ironically, those who wanted to tear America down by murdering its representative in Libya have strengthened my own sense of being an American.

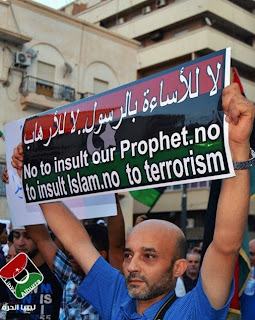

Shortly after learning of the death of the American ambassador in Benghazi, I began to see photos from the streets of Libya’s capital, expressing the sorrow of ordinary Libyans. It was a good reminder for me that the attacks of a small group of extremists does not necessarily represent the feelings of the people of Libya as a whole. In the context of the intense emotions I am feeling, these apologies extended by ordinary Libyans mean a lot.

What am I experiencing when I am drawn into this kind of collective mourning and euphoria? While I have rarely experienced these feelings as part of a nation-state, I have felt them regularly in religious life. Paul talks about how when we are animated by the Spirit of Christ, we are drawn into one body. Outside of the community of faith, I have also experienced this sensation in mass social movements, particularly during the early months of Occupy Wall Street and Occupy DC.

In moments like these – whether in the context of the Church, broad social movements or the nation-state – it is clear that human beings are made for connection. We are built to be integrated into a whole that is greater than our individual selves. In the Christian understanding, this integration takes place on the “spiritual” plane. When groups of individuals are united together, there is “spirit” involved. For the Church, the spirit that unites us is the Holy Spirit of Jesus. But it stands to reason that there are other spirits that draw people together.

Here are some questions that I am chewing on: What is the spirit that animates nationalism? What kind of spirit am I being drawn into when I feel shared pain and solidarity with all Americans? What is at work when I sense that an injury to one is an injury to all? How can I remain aware of what spirit I am being caught up in at any given moment – and how can I avoid being seduced by spirits that lead to factionalism, hatred and violence?